In General

In my last article, I set forth principles to which every classical rider must adhere to ride his/her horse with agility, beautifully, and in balance and harmony. However, there are some things that can go wrong during the training process. Podhajsky touches on these faults which I will outline in this article.

To begin with, it’s worth mentioning the role of haste and impatience in the training of the horse. and their detrimental effects. Klaus Balkenhol, coach of the United States Equestrian Team, 2002-2008, has commented on a disturbing trend in which riders and owners push their horses too quickly into competition to the detriment not only of the theory but the health of the horse. See his comments here.

This trend is nothing new. Holbein in his Directives (1898) pointed out in the introduction to Podhajsky’s Complete Training of Horse and Rider that the shorter time allowed for training and the universal demand for speed has caused a decline in the art of riding throughout the various armies (p.24). Holbein goes further by saying that by making High School (advanced riding) so artificial, a gap has been created between school riding (training) and campaign riding (application) to the disadvantage of both (p.26).

Philippe Karl in his Twisted Truths of Modern Dressage (2008) has pointed out that

“The proprtion of horses that the system irremediably ruins in the first years of their ‘use’ is enormous. Official authorities claim not to have figures on the subject. We must use private sources. For example, a study presented at Giesse in 1977 by Dr. H. Gutekunst under the guidance of Professor Dr. J. Nassal gave the following information:

“Statistics from the Federal Property Insurance Company concerning saddle horses in the Republic of Germany between 1971 and 1974 study covering 6,464 cases.

Average usage of saddle and competition horses: 5.54 years.

Average age of retirement: between 8 and 9 years.

Main causes of retirement: problems with the locomotor system (premature wearing due to early and irregular usage).

In the age group from 5 to 12 years old: 76.43% of damage, 65.64% of deaths, 74.56% of emergency euthanasia, 77.81% of retirement for definitive loss of aptitude.”

As a contemporary example of the above statistics, Podhajsaky notes that it has become the habit nowadays to demand spectacular movements like the passage before the horse has had enough training in the basic exercises (p.39).

The examples above describe exploitation rather than faults in training per se. However bad training is an expression of exploitation, in my opinion.

I Things That Can Go Wrong With Movement and the Sequence of Steps

A. In The Walk

It is a fault if the horse moves forward with both legs of one side at the same time so only two hoof beats are heard (p.32) This is known as a lateralized walk.

It is also a fault when the legs are not put forward in the same rhythm and the same length of stride, or he makes hasty steps. This could also be called an “ambling walk.”

B. In The Trot

Podhajsky says that the trot is the most important gait for training horse and rider. Faults that creep in i the trot will most likely have a bad influence on the other paces.

One of the most common faults in the trot is the hurried steps of the forelegs in which they reach the ground before the diagonal hind leg so that two separate hoof beats are heard instead of one. These horses carry a greater proportion of their weight and that of their rider on their shoulders. If the hind leg is put down before the diagonal foreleg and again two hoof beats are heard, it is known as a “hasty hind leg.”

In working towards cadence, or a more elevated rhythm, it would be wrong to allow the steps to become slower and hovering in the shortened trot (p.35). This leads to the so-called “passagey trot” so often seen in modern competitive dressage where rhythm is lost.

Cadence without rhythm is inconceivable. If rhythm is lost, the trot will become unlovely and the horse will lose his brilliance and beauty (p.35). Cadence is meant to be lively and elevated.

It is a fault when the horse does not bring his hind legs sufficiently under the body and appears to make a longer stride with his forelegs, which accordingly have to be withdrawn to equal the stride of the hind legs. In terms of riding, the horse promises more in front than he can show with his hindquarters.

In the picture below, Podhajsky’s description of the above fault seems to have become a prediction of an all-too-often-seen habit in today’s dressage performances. Note that the trajectory of the front and hind legs is not parallel as it should be. This is shown by the the red lines demarking the angles.

Hyperextension of the Front Legs at the Trot

Contrast the above picture with the picture below in which the angles of the front and hind legs match, as they should. This is a relaxed horse with a more open head position.

Correct Leg Angles at the Trot

In The Piaffe

The piaffe is incorrect if the legs are not raised diagonally or regularly or only the forelegs are lifted while the hind legs remain touching the ground. It is equally incorrect if the hind legs are raised in an exaggerated manner while the forelegs hardly move at all. In none of these cases, will the horse be able to make an immediate transition to the trot, which is the surest sign the piaffe training was incorrect (p.38).

Another fault is when the horse moves his legs sideways (often seen in the circus) instead of in the direction of movement. It is incorrect if he crosses his forelegs and weaves from one side to the other.

In the Passage

If the hind legs do not step sufficiently under the body and do not carry enough weight, they will come to the ground before the diagonal forelegs and the brilliance of the movement will be lost (p.38).

Furthermore, it is a fault if the steps of the hind legs are uneven, or one hind leg steps higher under the body than the other.

Finally, it would be a fault, according to Podhajsky, if the trot appears to hover and does not go sufficiently forward.

C. In the Canter

The canter is incorrect if four hoof beats are heard (a four-beat canter) instead of three. This happens when the hind leg is put down before the corresponding diagonal foreleg and when there is a lack of impulsion by incorrect collection and the horse does not canter with sufficient elevation. He appears to hobble along (p.35). Only in the racing gallop do we hear four hoof beats.

II Things That Can Go Wrong With the Form the Horse Should Take To Move in Balance

-Faults in Regard to Balance

Podhajsky reminds us that most horses carry a greater proportion of their weight on the forehand. As a result, the hind legs will push the weight more than they carry it. This is a fault which must be corrected if the paces are to be light and elastic (p.41)

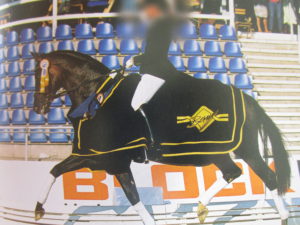

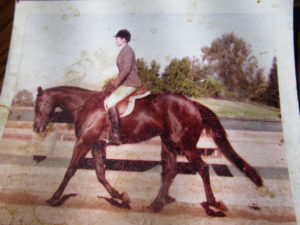

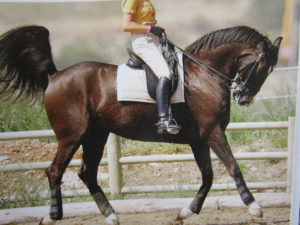

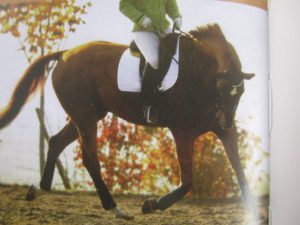

The pictures below show a couple of well trained horses that are nevertheless on the forehand. This fault tends to show up on western horses and hunters. Contrast the first two pictures with a horse’s natural carriage in the third picture as he moves without a rider. Also, note the correct carriage for a riding horse in the last picture. Hunters, by the way, are an American invention. In Europe, you will not see jumping horses divided into hunter and jumper classes. They are all jumpers trained classically.

Extreme forehand tendency

Nice Horse; Still on the Forehand

A Horse’s Natural Carriage

Correct Position of the Head for Carrying a Rider

-Faults in Regard to Contact with the Bit;Throughness

Faults in Contact effect head position, straightness, and balance.

Contact may be uneven when the horse takes firmer contact on one side (the stiff side) and not enough contact on the other (the hollow side). The rider will recognize this as the rein will not touch the neck on the hollow side whereas it lies close to the neck on the stiff side. On the hollow side, the horse will anticipate the action of the rein and bend that way (p.44).

Straightness is effected as the horse will become crooked with uneven contact in the reins (p.46).

Furthermore, if the horse accepts the bit on one side only (the stiff side), the action of the rein will escape on the opposte side and lose its effect (p. 48). That is, the action of the rein will not go through the body on the hollow side, effecting throughness.

-Faults in Regard to Head Position; Faulty Contact

Above the Bit.

The horse carries his head too high and the angle of the face is too far in front of the perpendicular. This happens with horses that are weak in the back and are uncomfortable by the weight of the rider.

Care must be taken in such a case that the under part of the neck does not become convex, producing a bulge as with goiter. This can occur when the reins are incorrectly applied (p.49).

Behind the Bit; Incorrect Understanding of Longitudinal Bend

The horse brings the angle of the face too far back behind the vertical. This may be caused by asking for collection too soon without first obtaining the necessary impulsion or because the hands are too strong (42).

Unfortunately, horses being ridden behind the bit has become a habit in modern dressage competitions. Dr. Gerd Hueschmann discusses this tendency at length in his book Tug of War: Classical Versus “Modern” Dressage. He calls it “hyperflexion” or “rollkur.” The pictures below show horses in this frame at international competitions. Hueschmann argues that this obsession with a longitudinal bend of the front end of a horse ruins the gaits and is generally harmful to the horse.

Horse Behind the Bit;Hyperflexion

Horse hyperflexed or behind the bit

Podhajsky, on the other hand, defines longitudinal bend as the bend that occurs in the three joints of the hind legs (hock, stifle, fetlock) as they assume more weight bearing capacity. He does this to bring the reader’s attention to the engine for collection – – the hind legs. The riders above in hyperflexion seemed to have directed their focus on the wrong end of the horse.

Conclusion

I have reviewed some problems which can occur in the training of the horse when the theory set out by Alois Podhajsky is incorrectly applied or not applied at all.

I invite the reader to leave a comment below on these problems as I’ve reviewed them here.

I would also like to remind the reader that one thing we must remember when working with horses, or any animal for that matter, is “animal dignity.” I quote now from Prof. Dr. phil. Peter Kunzmann who wrote the following in the foreword to Dr. Heuschmann’s book cited above:

“It (animal dignity) goes beyond questions regarding animal welfare; it is about having insights into each animal’s own intrinsic value and individual nature, and respecting it. The animal’s nature should be allowed to ‘unfold.’ and this unfolding must not be obstructed, prevented, or broken by mankind’s demands and power over it……….See horses first and foremost as horses, and then (and only then) as the status symbols, breeding successes, or financial assets they might also be.” (p.14)