INTRODUCTION

This article discusses principles of dressage developed by master Alois Podhajsky. It builds on two previous articles on this website. The first of these you can find here. The second one here.

Alois Podhajsky is the father of classical equitation in the modern era. He was born in Austro-Hungary and became the Director of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna in 1939. The Spanish Riding School is the home of the famous white Lipizzaner stallions and has become the home of classical riding handed down through the centuries. A review of its history may be found here.

Podhajsky describes principles of classical dressage in his book The Complete Training of Horse and Rider in the Principles of Classical Horsemanship (1967). I will be referring to this book to further develop our understanding of dressage and specifically to Chapter II “The Definitions of the Classical Art of Riding” (p.29-69). However, I have taken some liberties and classified Podhajsky’s “definitions” somewhat differently. For example, Podhajsky goes into “rewards” and “punishments”; I will not discuss those at least in this article. Also, he talks about “half halts,” which I would rather talk about in an article on training. What I do here is pull out principles which directly relate to the scales of training which we use today. See my article on this here,

–Why Theory is Important

Podhajsky describes theory as essential because it is the knowledge upon which the practice, or the ability, is built. Both are needed; one is not complete without the other. Practice is proof of the theory, but theory takes precedence over action (p.20).

The principles (of a theory) are the result of accumulated experiences which serve as instructions for riders of today and prevent them from wasting their time with unnecessary experiments. On the other hand, there are no rules for the difficulties which may appear (p.30).

–Harmony as the Ideal of Classical Riding

Harmony is the ideal of classical riding because in its highest form, it is demonstrated by aids (instructions to the horse) which are imperceptible or invisible to the observer, the two creatures moving as one (p.65).

Podhasky explains that it is the rider who aids the horse in understanding him and achieving the ideal of harmony. And it is this mutual understanding between the commanding partner and the executing partner, as Podhajsky would say, that leads to harmony between the two. So what are the principles or theory that the rider must strive for to develop harmony with his/her horse?

Besides a knowledge of the physiology and psychology of the horse, Podhajsky maintains that the rider must have a clear notion of the theory of movement and balance. The former means an exact knowledge of the sequence of steps; the latter a knowledge of how the steps should be executed and the form a horse should adopt to be able to move in balance (under a rider) (p.30).

I TOWARDS A THEORY OF MOVEMENT; AN EXACT KNOWLEDGE OF THE SEQUENCE OF STEPS

A basic requirement of dressage is purity of the paces or gaits or a regular rhythm. This regularity of rhythm combined with the longitudinal bend of the three joints of the hind legs during the steps eventually develops into an elastic spring felt as pleasant movement by the rider.

A. How Gaits or Paces May be Characterized.

1. The Pace/Gait Itself.

The pace or gait refers to the sequence of steps.

2. Tempo.

Tempo refers to the length of stride or the amount of ground covered per minute within the movements of the various paces. The tempo may be ordinary, collected (shortened), or extended (lengthened), and it may be changed. But a main objective of training is to be able to maintain a regular rhythm regardless of tempo. (p.31).

3. Cadence.

Cadence is a shortening of the stride, or tempo, while maintaining the same rhythm. This requires the legs to be raised higher or become more elevated (p.35).

B. The Different Gaits or Paces of the Horse

1. The Walk

The walk is a four-beat gait. There are typically three tempos for the walk:

a. Ordinary, or working walk

b. Collected walk, which has a shorter stride

c. Extended walk, which has a longer stride

Podhajsky notes that the elevation of the stride may change with the different tempos in the walk. However, there is no moment of suspension. Furthermore, the horse may not drag his feet or take hasty steps.

2. The Trot

The trot is a four-beat gait with one diagonal pair of legs contacting the ground while the other pair is in the air. So there is a moment of suspension in between one diagonal pair hitting the ground and the other. The duration of suspension is shortest in the shortened tempo trot and longest in the extended tempo.

There are four tempos to the trot:

a. Ordinary trot.

This is a forward, reaching trot used when riding in the country.

b. Working trot.

This is a tempo between ordinary and collected trot used to acquaint young horses with a more collected trot.

c. Collected trot.

This is a shortened trot used in the arena.

1). Piaffe. This is a cadenced collected trot on the spot while the horse steps from one diagonal pair of legs to the other with a moment of suspension in between. The piaffe is ideal if the forelegs are raised so that the forearm becomes almost horizontal to the ground and the hoof of the suspended hind leg is raised above the fetlock (joint above the hoof) of the leg on the ground.

A correct piaffe has been developed from a forward urge which has been checked (p, 38).

2). Passage. This is a cadenced collected trot in which the horse swings proudly forward from one pair of diagonal legs to the other and suspends the pair of diagonal legs in the air higher and for a longer period than in the regular trot. In this pace, suspension attains the longest duration. It demands a strong, thoroughly trained horse who is master of his balance and free from any tension (p. 38). It appears like a collected trot in slow motion (p.39).

d. Extended trot.

In the extended trot, the extension of the horse’s legs are stretched to the utmost.

Rein Back. The legs move in the sequence of the trot- – that is, two beats – -as he steps backwards. The horse should not drag his feet along the ground.

3. The Canter

The canter is a three-beat gait. It is known as right or left depending upon which foreleg is leading. In the right-lead canter, for example, the left hind leg is on the ground first, followed by the right hind and the left fore together, and finally the right foreleg. There is a moment of suspension before the next sequence of steps,

Podhajsky defines four tempos for the canter:

a. Ordinary canter.

This is for cross-country riding which can be moved to the extended canter.

b. Extended canter.

Also called a hand gallop. This is still a three-beat gait but covers more ground.

c. Working canter.

This is a three-beat gait between ordinary and collected canter used in the arena.

d. Collected canter.

This is a shortened canter tempo used in the arena.

Counter canter. The horse is in a canter lead opposite to the one he would normally use in the direction he’s going. So the horse might be traveling right around the arena –that is, with the center of the arena to the right of the rider’s shoulder–but be in a left-lead counter canter. He would be leading with the left foreleg.

C. Lateral Work

Lateral work (half pass) can be performed in all three paces or gaits — walk, trot, and canter. The horse moves forwards and sideways, the legs in movement crossing over those on the ground. The sequence of steps remains the same for all three gaits (p.36).

II TOWARDS A THEORY OF STEPS, THEIR EXECUTION, AND THE FORM A HORSE SHOULD ADOPT TO BE ABLE TO MOVE IN BALANCE

Podhajsky maintains that perfect balance is given partly by nature but can be improved by systematic training.

By nature the forelegs have to bear the greater proportion of the horse’s weight as they have to carry the neck and the head. But the weight of the rider throws additional weight on the forehand, which makes matters difficult for the horse.

The object of training therefore will be to help the horse achieve better balance with a rider by making the hindquarters carry a greater proportion of the weight. The forehand is thus relieved since some of the weight is transferred from the shoulders to the hindquarters. This is attained by collection, whereby the horse’s hind legs step further under his body, and by a concurrent raising of his forehand and lowering of his hindquarters (achieved by longitudinal bend discussed below).

Besides physical balance, mental balance is necessary for the horse to work consistently and quietly (p.41). Balance, furthermore, is the requirement for pure and impulsive paces or gaits.

-FORWARD

Podhajsky explains that the rider who concentrates on riding his horse forward on the bit, making him step well under the body with his hind legs — so he can raise his forehand correctly — will achieve much better success than a rider who thinks only of raising his horse’s head with the reins without pushing him forward. (p.49)

Riding forward is the essence of correct training (p. 56,62).

-STRAIGHT

“Straight,” according to Podhajsky, means that the hind feet follow the track of the forefeet.

Under the weight of the rider, the horse will show an inclination to be crooked; that is, the horse may step to the side or may have uneven contact on both sides. Only when the horse is straight will it be possible by collection, to make the hindquarters carry a greater proportion of the weight.

A straight horse traveling in an arena will have a slight degree of bend to the inside (slight shoulder fore position) (p.50).

A straight horse above; a crooked horse below.

A fundamental rule of equitation is straighten your horse and ride him forward (p.46)

-CONTACT WITH THE BIT

The horse is on the bit, according to Podhajsky, or correctly in contact with the bit when he seeks a soft connection with the bars of his mouth on the bit and the rider’s hands. The horse is neither above the bit (carrying his head too high) nor behind it (carrying his head too low) but correctly in contact when he is in absolute balance; he carries himself and does not seek support from the reins. So balance and contact are complementary. The better the balance, the better the contact. On the other hand, correct contact will improve balance and the suppleness of the horse.

When the rider has correct contact with the horse’s mouth, s/he should have the feeling that s/he is connected to the horse’s mouth by means of an elastic ribbon (p.41)

-POSITION OF THE HEAD

Correct position of the head as well as being the goal of good riding is the result of good riding expressed through contact and balance. Podhajsky might argue that it is the proof of the pudding. Both contact and balance are developed by riding the horse briskly forward, making it easier for the horse to follow the commands of the rider given through the reins. Good contact enables head position; the position and carriage of the head conversely become of the utmost importance for balance (p.44-45).

The ultimate objective is for the poll to be at the highest point of an arched neck; the horse’s head and neck will be raised to a position in which a line drawn from the nose to the hip will be parallel to the ground.

When moving on a straight line, the position of the head and neck must be straight. In a turn, the horse must be bent from head to tail in the degree defined by the arc of the circle or turn. The rider should see the horse’s inside eye. The neck must not be bent more than the whole body, and the horse yields in the gullet, or throat, not in the muscles of his neck. The ears must be on the same level lest the head be tilted. A well-trained horse has a position slightly to the inside of the arena.

Correct Position of the Head

Behind the Bit on the Left; Above the Bit on the Right

-THROUGHNESS

Podhajsky describes this as the “action of the rein going through the body of the horse” as it passes through the horse’s neck and back. This action is brought about by the rider squeezing the rein or reins with his hand(s). The horse bends through a turn or in a lateral movement by this action, putting more weight on the hind leg of the same side. See Bend/Suppleness below. Throughness is the short-hand term we use today to describe such an effect. Throughness for longitudinal bend is possible only when the horse is straight and takes an even contact with the bit. The horse steps with his hind legs under the elastic back and through the elastic neck into the rein of the same side (p.47).

-BEND/SUPPLENESS

There are two types of bend according to Podhajsky – – lateral and longitudinal bend.

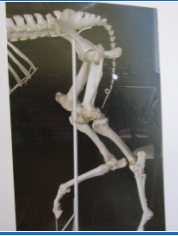

The lateral bend refers to the regular even curve from poll to tail that the horse’s body should assume while traveling on the arc of a circle or through the turn of a corner.The longitudinal bend refers to the bending of the three joints of the hind legs accompanied by flexing the gullet or throat equally on both sides (p.51).

Podhajsky says that the lateral bend is easier to obtain and therefore should be practiced first. A correct lateral bend will show the ribs on the inside of the body to be somewhat compressed while the body is arched to the outside (p.50). This happens through different degrees of bend depending on whether one is riding large or small circles and turns. Lateral bend enables balance by making it easier for the horse to put his center of gravity below that of his rider.

The longitudinal bend comes after the horse has mastered the lateral bend. The correct bend of the hind legs must be brought about by all three joints being bent equally and to the same degree (p.51). These joints include the hip joint, stifle and hock. When all three joints of the hind legs are equally bent, they impart a suppleness to the gaits and elastic springiness which the rider feels as a pleasant movement of his horse.

Three Joints of the Hind Leg: Hip Joint, Stifle, Hock

Both lateral and longitudinal bend are necessary to enhance the suppleness of the horse while suppleness, in turn, increases the efficacy of the bend.

Suppleness brought about by longitudinal bend especially improves balance through increased collection and smoother contact with the bit.

-IMPULSION

Podhajsky says that it is impulsion, or the action and energy from the hindquarters, that is necessary to raise the head and neck necessary for balance in collection (p.48). In modern dressage circles, this may also be described as increased thrust from the hindquarters.

The hind legs, on which the brilliance of the paces depends, must act with more energy, and the tracks of the hind feet must step into or in front of those made by the forefeet. In fact, the hind legs may be compared to the engine of a motor car which produces the power for movement (p.48).

Note the engagement of the right hind leg

Impulsion is an objective of dressage and may be described as being developed from the principles which precede it.

-COLLECTION

Podhajsky says that a horse in collection must step with his hind legs well under his body. This is recognized by the fact that the tracks of the hind feet come into or in front of those of the forefeet. Collection makes the horse arch his back correctly and carry his head higher, thus becoming shorter in his body (p.46).

Collection is necessary for work in shortened tempo paces and for the performance of short turns and smooth halts. It is necessary for advanced training as well as it makes the hindquarters carry a greater proportion of the weight, thus relieving the forehand and preventing the horse from wearing out his forelegs prematurely. Correct collection will be possible only when the horse is straight, balanced, and in contact with the bit. On the other hand, collection increases balance thus improving contact, develops paces, and establishes obedience (p.47).

Collection From Longitudinal Bending Without the Bit.

We will see as we proceed through the principles or elements of dressage that an end result is harmony in collection.

CONCLUSION

This article has presented the dressage principles of classical riding master Alois Podhajsky that can be useful across riding disciplines.

Podhajsky has offered the “why” and the “what” of classical dressage; that is, why we do what we do and what we hope to achieve by it.

We do these things to achieve harmony with our horses; that is, to enable the ability of two creatures to work together as one unit. the “what” of dressage training are the principles we strive for in order to assist the goal of harmony. These principles include

- a knowledge of the sequence of steps

- principles for the the execution of the steps and the form a horse should adopt while doing them in balance. These are as follows:

- forward

- straight

- contact

- position of the head

- throughness

- bend/suppleness

- impulsion

- collection

Of course the challenge for the rider is being able to put these principles into action while riding the horse. It is the effectiveness of the rider which achieves this and which will be the subject of another article.

CALL TO ACTION

How do you see the blending of these principles, their order, their importance?

Excellent post! I really like how you provided links and background information on the subject matter. This is an interesting topic especially with the Kentucky Derby coming up this weekend, which invites the question, do the same theories apply to race-horse jockeys as well? Horses are such beautiful animals and I find it fascinating that humans thought to tame them from the wild and make them useful and elegant. You did very well here placing cadences into context, makes me want to get on a horse and put these theories to the test. Thank you this post is much appreciated.

Thanks so much for your comment. Actually, Podhajsky’s theory wouldn’t work for race horses while they’re racing. They thrown themselves on the forehand to get out there and run like heck. Thoroughbreds retrained for normal riding, however, could definitely benefit from Podhajsky’s approach. Carole

Dear Carole,

May I not congratulate you on your persistence in creating this detailed and helpful post. Any person who devotes that much time must of necessity make discoveries of great value to others. I got great insights from your post.

I love horses and I love horse riding. I watched the movie “Dreamer” since then horses and learning about horse ridding is my dream. At the moment all I do is just browse and learn about it and one day my dream will come true.

Indeed, both Theory and Practice is important, theory will save our time and effort and we can avoid mistakes. Your post can be used as a guide in riding disciplines. I will have to go back to it a few times just to grasp all of that information. You definitely have done your research. I was not expecting so much information, to tell the truth.

The images you shared are very helpful in understanding and give a clear picture (idea). After reading your post I got the urge to read “Complete Training of Horse and Rider: In the Principles of Classical Horsemanship”.

Great information, you have really given a lot of value here and I really enjoyed the content and in the manner that you presented.

I am bookmarking your post for future reference.

Much Success!

Paul

Thanks so much for your input, Paul. Please keep in touch. Carole

Thank you for this post about dressage. I love horses as they are both beautiful and intelligent animals. I enjoyed learning about the form and steps both horse and rider must take in order to execute properly.

I admit I am a novice but the information you have provided will come handy the next time I watch horses in competition.

Proud papa of two,

Jody

Thanks, Jody.

After rereading my own article, I wish to include the following thoughts:

1. Podhajsky touched on the notion of mental balance. I think a good synonym for that might be “relaxation.”

2. As a rider, I must remind myself to keep the elements of theory in mind while riding the horse and working on the various patterns I’ve laid out for us.

3. There will be times during our work when I become distracted by something in our environment. I must remember not to become so distracted that I relinquish my responsibility of properly guiding the horse to do what I want.

4. I have thought about a process for forward when my horse does not respond to my first request. I would first use a light leg, then a heavier leg, and finally a touch with the whip to get his attention.

5. For proper contact, I remind myself not to keep my hands too low where the effect might be one of pulling rather than connection.

6. A good approach to suppleness I have found is some warmup exercises which include turns on the forehand, turns on the hindquarters, rein back, turns on the hindquarters with a counter bend.

7. Podhajsky seems to be referring only to half pass when he touches on lateral work in his discussion. Today in addition to half pass, the term “lateral work” might include shoulder in, haunches in, renvers, shoulders out.

8. When working towards harmony as a goal, we can only strive for it. When you experience it, it is a gift, a reward for all the time you’ve put into relationship with your horse. It is nothing less than a linking of souls, a unity of purpose and experience that feels like ecstasy. It is beyond words to describe, but I know it when I feel it. It has been fleeting with my different horses but unmistakable.